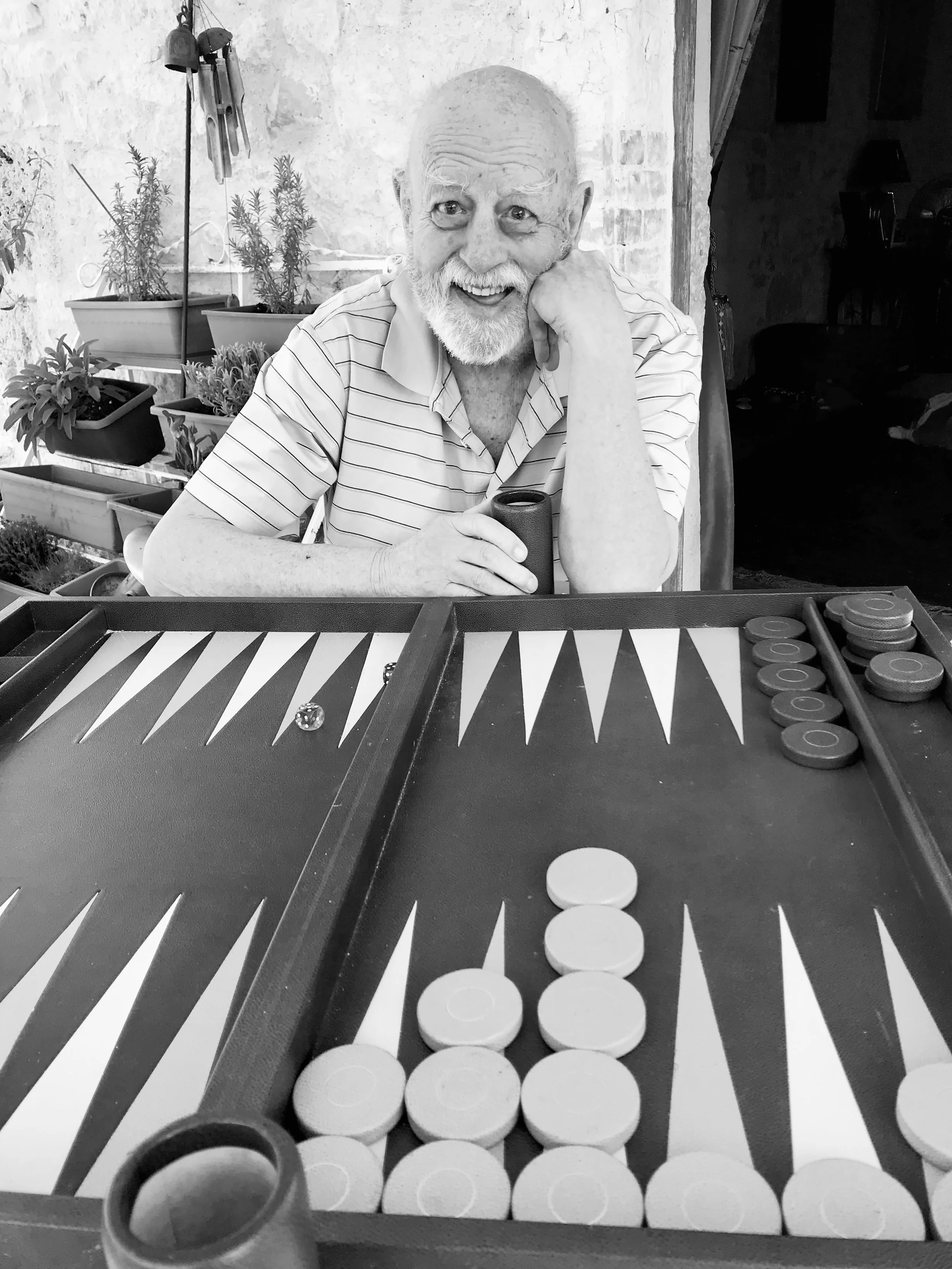

LIFE IS A GAME OF BACKGAMMON

People may remember Roger Whittaker as the whistling, guitar playing entertainer of the 1970/80s; the man who wore cardigans and beards as if they were patented by him; the crooner with such a melodious voice he made you believe honey could be ingested through your ears.

I remember him as the man who taught me the importance of continuing to roll the dice even when you might not get the numbers you want. He taught me the importance of taking risks, of coping with loss as well as victory, of competing with a smile in your heart, of growling when things go wrong – but not for long – of telling the truth and a thousand other things that I never got the chance to tell him he was responsible for. It doesn’t matter; he knew.

1981, a sweltering afternoon on holiday in Spain, I was seven years-old and frustrated by the time-wasting obsession enjoyed by adults known as Siesta. He spied me prowling the terracotta tiles of the villa and offered to teach me his favourite board game. As he deftly set up, he whispered, “Now, this right here is just like Life: 50% luck and 50% skill. You never win all the time, but you up your chances of winning more often if you have both.” From that day forth it was more than just a game for us, it was one of the ways we stopped the hectic-ness of life around us, one of the ways we sat down to check-in and talk openly without the embarrassment of looking each other in the eye. From my classroom dramas to his song lyric conundrums; and later my partners, jobs, children, and the thorny topic of the right time to retire. We played on holidays, on tour buses, even in the hospital after numerous surgeries that he brushed off like they were a trip to the barbers. Nowadays, I can’t look at a backgammon board without thinking of the human bulldog who would growl at your win and would put it all down to luck, while beaming with pride that you had bettered him.

The start of each backgammon competition is an adventure and Roger Whittaker was nothing if not the ultimate adventurer, perhaps because of his upbringing. Kenya was his birthplace and when he wrote My Land is Kenya, he meant the people, and I cannot tell you the pride I felt to hear him speak fluent Swahili to fellow Africans. For Dad, going on safari was akin to camping in a Cotswold field with a tent and a bucket of water. I will never forget a time we were out in the bush and he tried to guide a swarm of attacking killer bees away from our jeep by literally running into the long grass, not stopping to consider how delectable he might be to a pride of peckish lions. Later that day, as he shivered from the venom in his back, and I enquired as to the pain, he said, “Ah, I’ve had worse.”

He never complained. He was a man who went out on stage the night before major back surgery and two days after. He asked life what it had in store for him and he faced it without fear. If you asked me who I’d invite to a fantasy dinner party, among my guests would be Dad, Elvis and Marcus Aurelius. I suspect they would recognise themselves in each other: the kind of people who endure adversity and come out greater for it.

Having survived a childhood that contained abandonment bad enough to be called abuse, he became determined to give his children a better one. There were five of us and he was often away on tour, so getting his attention when he was home was hard. But even when I thought he wasn’t looking he noticed.

1987, aged fourteen, my head had been hijacked by teen hormones. It was a time when being with family for Easter lunch was its own kind of special ops torture. Before I killed someone, I announced that I was going on a long walk and wouldn’t be back for, “literally hours… if at all.” In the cacophony of the twenty-something relatives no one seemed to notice my exit. No one but Dad, who jumped up and offered to join me. (Looking back, I think he used me as an excuse to get away too but for the purposes of this ode, let’s keep his intentions heroic). I think I said something along the lines of, “There’s no way you can keep up.” Huffing and tossing my hair, I donned my Walkman and marched ahead. Wearing his black velvet trilby, he kept a pace and wisely said nothing, not for the first hour and not for the second. We just walked in meditative silence. I, fuming over a sibling slight and an oldie hanger-on; he, smiling at his fiery child. Then, without me even realising he had worked his magic, the headphones were around my neck and we were talking as we marched. Slowly the march became a stroll and then it became an amble. He didn’t press me for details because he knew what was irritating me was simply teen ennui. He just wanted to accompany me on the journey for a little while and talk backgammon competitions that he would, “definitely win now because you’re too furious to focus.” It was only when we walked through the door and he removed his trilby to reveal the rivulets of black dye down his neck that I realised what it had cost him to keep up. Ten years later he confessed he’d had stents put in his heart two weeks prior to that epic eight-miler – news which turned me into a furious teen again. Oh, how we laughed.

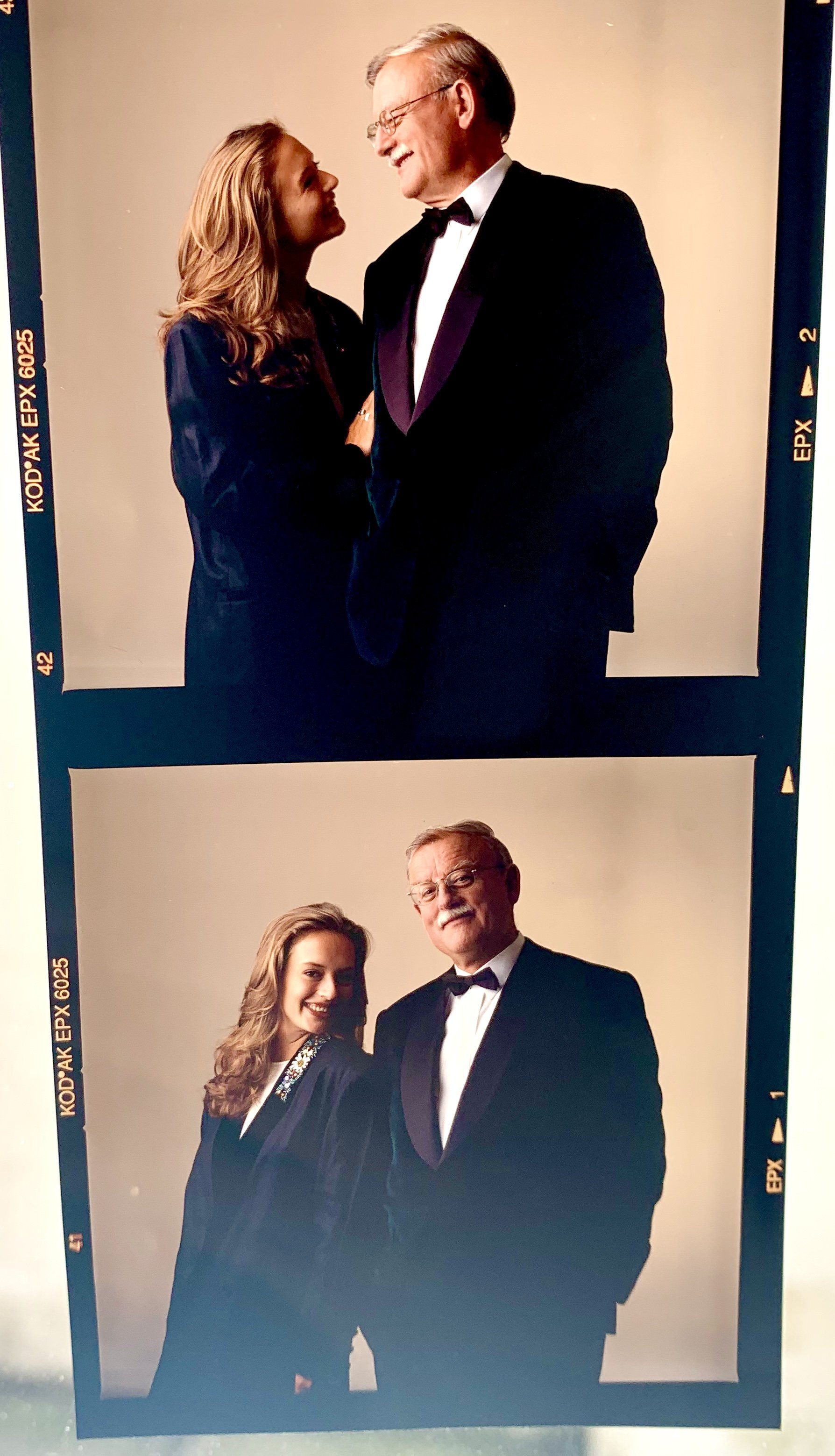

1990, we began touring together. He invited me to share the stage around the world with him simply because I was the loudest of the children and he thought it might shut me up. How wrong he was. At the time, as he showed me almost every state in America and most of Europe, I knew somewhere in abyss-level depths that I was blessed to experience it, but I was also semi-grateful (singing Alanis Morrisette at the top of my lungs after sound check to make it clear I was not in any way mainstream) and too young to appreciate how precious this time with him was. Now that he is gone, I would trade all the double sixes for the chance to sit with him backstage, both of us in full costume, playing backgammon and sipping tea, right up until the last second when the crew began to panic that we wouldn’t stop in time to step out with our mics on.

I’d like just one last roll of the dice Dad, one last move and that glint in your eye that says, “I double you.”

Dad played his last game of backgammon ever with my youngest brother. Alex, in a French hospital where he spent his dying weeks. The day he played he was as good as when he played Omar Sharif or Roger Moore, or me, who only ever won because, “You’re so bloody lucky!” But Dad, I hope it is also skill, skill you taught me, that I will take forward. Thank you for teaching us how to live, big man. I will miss you so much, as will your fans. Go play guitar with Elvis and tell Marcus Aurelius you had our backs when you raised us.

My heart is broken but Dad would hate to hear me complain about it, least of all to myself. So, onwards…

ROGER WHITTAKER. 1936-2023